09 October 2008

I had a very pleasant dinner at the wonderful “Fresh” vegetarian restaurant in Toronto on Tuesday evening. My friend and colleague, Prof Andrew Crane, and I met with Nai-wen Wong, a visitor from Taiwan, who is part of the CSR International network I run.

One of the stories from Nai-wen that I liked was how people in Taiwan are now being encouraged to bring their own chopsticks to restaurants, to save all the forests being cut down for disposable chopsticks. That sounds like a great environmental idea, with a cultural twist.

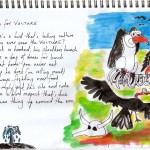

On Sunday, I was walking around Toronto Island Park when, to my unexpected surprise and delight, this guy on a Penny Farthing bicycle rode past me. The Penny Farthing – so called because of the relative size of the British penny next to the smaller farthing coin – was invented in the 1870s.

It got me thinking about our progress, or more accurately, lack of progress. For me, the Penny Farthing, which has hardly changed at all to become the modern bicycle more than 130 years later, is a perfect metaphor for our seeming lack of change in other areas.

I am thinking mostly about that other wheeled invention, the car. More specifically, the internal combustion engine car. The basic design has hardly changed over the past 100 years, even though we have tinkered to make it more efficient, safe and clean.

At one level, we might say that, like the bicycle, it’s because the basic design still works. So why change a winning formula? But does it really still work? Is spending hours in gridlocked traffic, or thousands dying in auto accidents, or pumping out pollution that causes asthma and climate change what “works”? Is that our definition of a winning formula?

But now we have hybrids and electric cars, I hear you say. True, and I am their biggest fan. They begin to solve some of the environmental and health problems, but they still keep us locked into the same basic design – a metal box, with an engine, on four wheels. Is that the best our fantasmagorical imagination can come up with?

A penny (farthing) for your thoughts, my dear …

11 October 2008

I’ve enjoyed a wonderful week in Toronto, with blue skies, lake views and Autumn leaves. It has me thinking about change. Would we appreciate autumn leaves as much if they were always always on display? Most likely not. It is the changes which help us to value life.