First published by World Economic Forum, 4 January, 2017.

In September 2016, SpaceX founder Elon Musk announced that we could have human missions to Mars as soon as 2022. One side effect – apart from pushing the frontiers of space travel – is that it will challenge us to design and perfect various systems of sustainable production. The reason is quite simple: Mars is a barren, hostile planet, where all life support systems – from food and water to air and energy – will need to be artificially made and sustained, mostly using the limited resources the crew take with them.

In essence, what Musk and his space cadets will be trying to do is replicate what nature already does for us here on earth: creating an intelligent biosystem that can endlessly reuse or recycle resources in a way that allows life to survive and, ultimately, to thrive. This is the same idea that underlies the philosophy of sustainable production – albeit that the motivation and applied context is different – and it is by no means a new idea.

1960s and 1970s: recognising limits

In the 1960s and 1970s, a growing cadre of concerned scientists, economists and activists began warning us of the dire impacts of the exponential growth in our consumption of resources and the associated proliferation of toxins, waste and pollution. This included the likes of: Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, 1962; Barbara Ward, author of Spaceship Earth, 1965; Buckminster Fuller, author of Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, 1969; and the Club of Rome, authors of the ground-breaking Limits to Growth study, 1972.

Ironically, “spaceship earth” thinking is exactly what Elon Musk and SpaceX are going to have to apply on Mars. It recognizes the fact that we live with limited resources on one planet that acts as a “metabolic, regenerating system”, as Fuller described it, or a “living, self-regulating organism” in the words of NASA scientist, James Lovelock, who named this the Gaia theory.

Unfortunately, we have been living (and hence producing and consuming), as if we were in a “cowboy economy”, rather than a “spaceman economy”, according to economist Kenneth Boulding. The cowboy, Boulding explained in 1966, is “symbolic of the illimitable plains and also associated with reckless, exploitative, romantic, and violent behaviour”, while the spaceman represents the recognition of the earth as “a single spaceship, without unlimited reservoirs of anything, either for extraction or for pollution.”

The logical conclusion of accepting such a world of limits is, says Boulding, that humanity “must find its place in a cyclical ecological system which is capable of continuous reproduction of material form even though it cannot escape having inputs of energy.” Walter Stahel, an architect and industrial analyst, added meat to the bones of Boulding’s vision by proposing, in a 1976 report to the European Commission, a “closed loop” approach to production processes. He called this “cradle to cradle” and developed it further through the Product Life Institute, which he founded in Geneva.

At the same time that these concerns and philosophical ideas were gaining traction, a more pragmatic solution was also emerging. At the World Energy Conference in 1963, Harold Smith proposed looking at a “cumulative energy concept”, which laid the foundations for life cycle analysis/assessment (LCA). In 1969, Coca-Cola extended this idea by assessing the resource and pollution impacts of different beverage containers. This emergent methodology became known as a Resource and Environmental Profile Analysis (REPA) in the US and as an Ecobalance in Europe.

1980s and 1990s: rethinking production

In the 1980s, while LCA gained momentum, a related concept called industrial ecology emerged. It was popularized in 1989 in a Scientific American article by Robert Frosch and Nicholas E. Gallopoulos, in which they declared: “Why would not our industrial system behave like an ecosystem, where the wastes of a species may be resources to another species? Why would not the outputs of an industry be the inputs of another, thus reducing use of raw materials, pollution, and saving on waste treatment?”

Industrial ecology, therefore, proposes that businesses should not only look at the life cycle impacts of individual products of individual companies, but also look for ways in which to link up with other businesses to minimize their impacts. The Danish industrial park in the city of Kalundborg is a classic example, where a power plant, oil refinery, pharmaceutical plant, plasterboard factory, enzyme manufacturer, waste management company and the city itself, all link together to share and utilize resources, by-products, energy and waste heat.

Meanwhile, life cycle assessment was becoming so popular that, in 1991, eleven state attorney generals in the US expressed concerns that the method was being used to make misleading green claims. This concern, together with pressure from elsewhere in the world, led to the development of two LCA standards as part of the International Standards Organization (ISO) 14000 series: ISO 14041:1998 on Life cycle assessment (goal and scope definition and inventory analysis); and ISO 14043:2000 on Life cycle interpretation.

Another concept that was gaining popularity around the same time was cleaner production, promoted by institutions like the OECD and UNIDO and resulting in the UNEP Declaration on Cleaner Production in 1998, in which they defined cleaner production as “the continuous application of an integrated, preventive strategy applied to processes, products and services in pursuit of economic, social, health, safety and environmental benefits.” To support its application, UNEP and UNIDO collaborated to set up a global network of National Cleaner Production Centres (NCPCs) in the 1990s.

2000s and 2010s: a new industrial revolution

In the new millennium cleaner production continued to spread, receiving further endorsement at the UN’s 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa. In 2010, UNEP and UNIDO also revived the NCPCs with the launch of a Resource Efficient and Cleaner Production network (RECPnet), with 41 founding members. This reinvigorated the practice of eco-efficiency, which the World Business Council for Sustainable Development had been championing since the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. It also introduced decoupling as a goal, referring to the need to delink economic growth and environmental degradation.

The EU government meanwhile began working with business to create product roadmapping as a way of systematizing the application of LCA in different industries. This culminated in the adoption, in 2003, of the EU’s Integrated Product Policy (IPP) to promote conducting LCAs with a view to potential policy interventions. Two familiar products with diverse impacts were chosen by the EU to demonstrate IPP: one was a mobile phone, put forward by Nokia; the other, a teak garden chair from Europe’s largest retailer, Carrefour.

While these multilateral efforts were going on, sustainable production really began to catch the imagination of business after architect William McDonough and chemist Michael Braungart published their book, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, in 2002. The cradle to cradle concept evolved from Braungart’s earlier work on lifecycle assessment with Germany’s Environmental Protection Encouragement Agency (EPEA), in which he grew disillusioned with the limitations of LCA.

Working with McDonough and applying their intelligent design insights to products and processes, they proposed a circular model of production in which there are continuous flows of biological nutrients (i.e. any renewable materials that can harmlessly go back to nature and be regenerated) and technical nutrients (i.e. any non-renewable, or manufactured materials that are not biodegradable, but remain useful if returned and reused in the production of products).

The future: towards a circular model

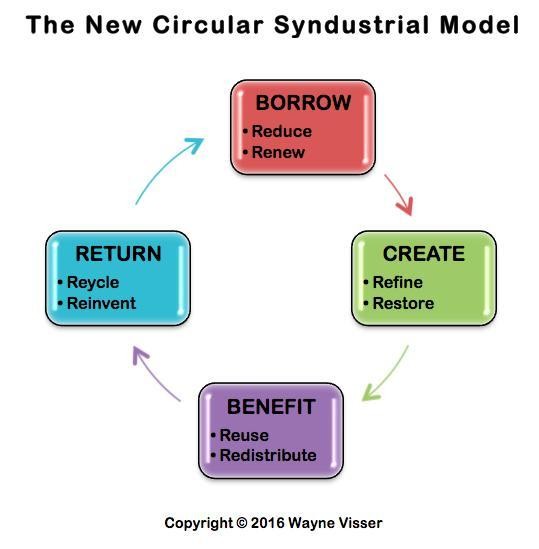

Today, “cradle to cradle” has been adapted, promoted and mainstreamed as a circular economy approach, which relies on sustainable production as a key link in the chain. The way I like to describe it is that we are now moving from an old industrial model, in which we take, make, use and waste, to a new “syndustrial” model (designed for industrial and ecological synergies), in which we borrow, create, benefit and return.

In the old linear industrial model, business and consumers take, make, use and waste. We take by depleting non-renewable resources and over-using renewable resources, and by striving for limitless economic growth. We make by producing any products and services that the market demands and persuading customers to buy and consume more. We use by buying more than needed, leading to over-consumption and by individually owning what could be shared. Finally, we waste by turning consumed products into trash and pollution and by creating toxins and impacts that harm people and nature.

By contrast, in the new circular “syndustrial” model, in which we design for industrial synergy, business and consumers borrow, create, benefit and return. We borrow by conserving all natural resources and increasing renewable resource use; and we create by designing and making products with no negative impact and innovating products with positive impact.

For example, Novamont, as an Italian producer of bio-based plastics and biodegradable plastics, has adopted a renew and refine strategy. Among their clients are the global coffee company Lavazza, which now sells compostable coffee capsules that Novamont have produced, which biodegrade within 20-40 days. Similarly, BioGen in the UK has a renew and restore strategy, producing renewable energy (biogas) from food waste and then using the waste slurry as bio-fertilizer, which has been shown to produce higher crop yields when compared with chemical fertilizers.

In the new “syndustrial” model, we benefit by extending a product’s life, by repairing and reusing and by leasing and sharing. We return by using end-of-first-life materials to recreate the same products and to create new products.

For example, Caterpillar, the heavy machinery company, has pursued a reuse strategy through their Remanufacturing Centre in South Africa (the second largest in the world), which is designed to rebuild “as new” CAT components for 20-60% less than the cost of replacing with new parts. Similarly, Dutch aWEARness in the Netherlands is one of the first textile companies to make fully “circular” clothes, thus demonstrating a true recycle strategy. For example, their WearEver suits are made from 100% recyclable polyester, which can be turned back into a suit at least 8 times, giving a total life for the materials of 40-50 years.

Tetrapak in Ecuador is part of a reinvent strategy, whereby beverage packaging waste is being upcycled by an independent company into a range of high quality products, such as corrugated roofing, furniture, tabletops and jewellery. Similarly, REDISA in South Africa is managing the recovery and reprocessing of 70% of waste tyres in South Africa into a variety of rubber and steel products, while creating more than 3,000 jobs.

These examples are all featured cases in a forthcoming documentary called Closing the Loop, due for release in 2017. By adopting and scaling these new business models, we can achieve a transformative sustainable and social responsibility, which focuses its activities on identifying and tackling the root causes of our present unsustainability and irresponsibility.

Citation and download

Visser, W. (2017) How changing sustainable production could take us to Mars, World Economic Forum, 4 Jan.