Creating Integrated Value: Beyond CSR and CSV to CIV

Paper by Wayne Visser & Chad Kymal

Abstract

Creating Integrated Value, or CIV, is an important evolution of the corporate responsibility and sustainability movement. It combines many of the ideas and practices already in circulation – like corporate social responsibility (CSR), sustainability and creating shared value (CSV) – but signals some important shifts, especially by focusing on integration and value creation. More than a new concept, CIV is a methodology for turning the proliferation of societal aspirations and stakeholder expectations – including numerous global guidelines, codes and standards covering the social, ethical and environmental responsibilities of business – into a credible corporate response, without undermining the viability of the business. Practically, CIV helps a company to integrate its response to stakeholder expectations (using materiality analysis) through its management systems (using best governance practices) and value chain linkages (using life cycle thinking). This integration is applied across critical processes in the business, such as governance and strategic planning, product/service development and delivery, and supply and customer chain management. Ultimately, CIV aims to be a tool for innovation and transformation, which will be essential if business is to become part of the solution to our global challenges, rather than part of the problem.

Creating Integrated Value (CIV) is a concept and practice that has emerged from a long tradition of thinking on the role of business in society. It has its roots in what many today call corporate (social) responsibility or CSR, corporate citizenship, business ethics and corporate sustainability. These ideas also have a long history, but can be seen to have evolved primarily along two strands – let’s call them streams of consciousness: the responsibility stream and the sustainability stream.

Two Streams Flowing into One

The responsibility stream had its origins in the mid-to-late 1800s, with industrialists like John D. Rockefeller and Dale Carnegie setting a precedent for community philanthropy, while others like John Cadbury and John H. Patterson seeded the employee welfare movement. Fast forward a hundred years or so, and we see the first social responsibility codes start to emerge, such as the Sullivan Principles in 1977, and the subsequent steady march of standardization, giving us SA 8000 (1997), ISO 26000 (2010) and many others.

The sustainability stream also started early, with air pollution regulation in the UK and land conservation in the USA in the 1870s. Fast forward by a century and we get the first Earth Day, Greenpeace and the UN Stockholm Conference on Environment and Development. By the 1980s and 1990s, we have the Brundtland definition of ‘sustainable development’ (1987), the Valdez Principles (1989, later called the CERES Principles) and the Rio Earth Summit (1992), tracking through to standards like ISO 14001 (1996).

Weaving Together a Plait

As these two movements of responsibility and sustainability gathered momentum, they naturally began to see their interconnectedness. Labour rights connected with human rights, quality connected with health and safety, community connected with supply chain, environment connected with productivity, and so on. The coining of the ‘triple bottom line’ of economic, social and environmental performance by John Elkington in 1994, and the introduction of the 10 principles of the UN Global Compact in 1999 reflected this trend.

We also saw integration start to happen at a more practical level. The ISO 9001 quality standard became the design template for ISO 14001 on environmental management and OHSAS 18001 on occupational health and safety. The Global Reporting Initiative and the Dow Jones Sustainability Index adopted the triple bottom line lens. Fair Trade certification incorporated economic, social and environmental concerns, and even social responsibility evolved into a more holistic concept, now encapsulated in the 7 core subjects[1] of ISO 26000.

Thinking Outside the Box

At every stage in this process, there have been those who have challenged our understanding of the scope and ambition of corporate responsibility and sustainability. Ed Freeman introduced us to stakeholder theory in 1984, John Elkington to the ‘triple bottom line’ in 1994, Rosabeth Moss Kanter to ‘social innovation’ in 1999, Jed Emerson to ‘blended value’ in 2000, C.K. Prahalad and Stuart Hart to ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (BOP) inclusive markets in 2004, and Michael Porter and Mark Kramer to ‘creating shared value’ (CSV) in 2011.

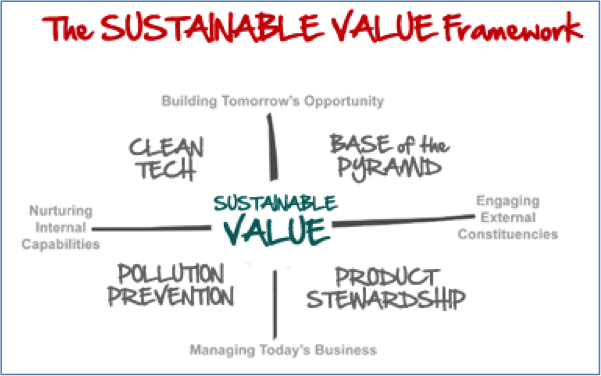

Typically, these new conceptions build on what went before, but call for greater integration and an expansion of the potential of business to make positive impacts. For example, Hart’s ‘sustainable value’ framework (2011) incorporates pollution prevention, product stewardship, base of the pyramid (BOP) and clean tech. Emerson’s ‘blended value’, much like Elkington’s ‘triple bottom line’ looks for an overlap between profit and social and environmental targets, while Porter and Kramer’s CSV focuses on synergies between economic and social goals.

Figure 1 – Sustainable Value

Source: Hart, Stuart L. (2011). Sustainable Value. Retrieved from http://www.stuartlhart.com/sustainablevalue.html

The ‘How To’ of Integration

Creating Integrated Value (CIV) takes inspiration from all of the thought pioneers that have gone before and tries to take the next step. CIV is not so much a new idea – as the longstanding trend towards integration and the ubiquitous call for embedding of standards testifies – but rather an attempt to work out the ‘how to’ of integration. When companies are faced with a proliferation of standards (Standards Map alone profiles over 150 sustainability standards) and the multiplication of stakeholder expectations, how can they sensibly respond?

We have analysed some of the most important global guidelines, codes and standards covering the social, ethical and environmental responsibilities of business – such as the UN Global Compact, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, ISO 26000, GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines (G4), IIRC Integrated Reporting Guidelines, SA 8000, UN Business & Human Rights Framework and Dow Jones Sustainability Index.

What we see are large areas of overlap in these guidelines, codes and standards across what we might call the S2QE3LCH2 issues, namely:

- S2: Safety & Social issues

- Q: Quality issues

- E3: Environmental, Economic and Ethical issues

- L: Labor issues

- C: Carbon or Climate issues

- H2: Health and Human rights issues

Our experience of working with business shows that most companies respond piecemeal to this diversity and complexity of S2QE3LCH2 issues (let’s call them SQELCH for short). A few large corporations use a management systems approach to embed the requirements of whatever codes and standards they have signed up to. Even, so they tend to do this in silos – one set of people and systems for quality, another for health and safety, another for environment, and still others for employees, supply chain management and community issues.

Knocking Down the Silos

CIV, therefore, is about knocking down the silos and finding ways to integrate across the business. In short, CIV helps a company to integrate its response to stakeholder expectations (using materiality analysis) through its management systems (using best governance practices) and value chain linkages (using life cycle thinking[2]). This integration is applied across critical processes in the business, such as governance and strategic planning, product/service development and delivery, and supply and customer chain management.

And what about value? Most crucially, CIV builds in an innovation step, so that redesigning products and processes to deliver solutions to the biggest social and environmental challenges we face can create new value. CIV also brings multiple business benefits, from reducing risks, costs, liabilities and audit fatigue to improving reputation, revenues, employee motivation, customer satisfaction and stakeholder relations.

Pursuing Transformational Goals

Our experience with implementing and integrating existing standards like ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 convinces us that, in order for CIV to work, leaders need to step up and create transformational goals. Without ambition ‘baked in’ to CIV adoption, the resulting incremental improvements will be no match for the scale and urgency of the global social and environmental crises we face, such as climate change and growing inequality.

One of the most exciting transformational agendas right now is the Net Zero/Net Positive movement[3], which extends the ‘zero’ mind-set of total quality management to other economic, social and environmental performance areas. For example, we see companies targeting zero waste, water and carbon; zero defects, accidents and missed customer commitments; and zero corruption, labour infringements and human rights violations. These kinds of zero stretch goals define what it means to be world class today.

Stepping Up To Change

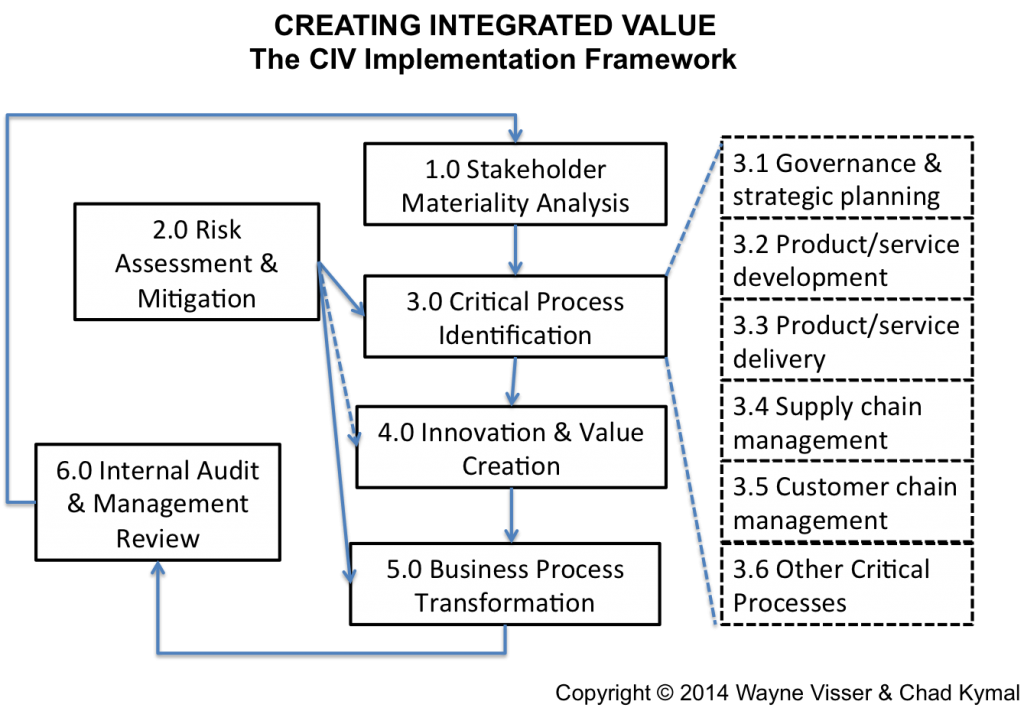

In practice, CIV implementation is a 6-step process, which we can be described as: 1) Listen Up! (stakeholder materiality), 2) Look Out! (integrated risk), 3) Dig Down! (critical processes), 4) Aim High! (innovation & value); 5) Line Up! (systems alignment); and Think Again! (audit & review). Each step is captured in Figure 2 and briefly explained below. Of course, the process must also remain flexible enough to be adapted to each company context and to different industry sectors.

Figure 2 – Creating Integrated Value

Source: Wayne Visser and Chad Kymal (2014)

Step 1: Listen Up! (Stakeholder Materiality)

The first step of the CIV process is Stakeholder Materiality Analysis, which systematically identifies and prioritises all stakeholders – including customers, employees, shareholders, suppliers, regulators, communities and others – before mapping their needs and expectations and analysing their materiality to the business. This includes aligning with the strategic objectives of the organization and then driving through to result measurables, key processes and process measurables.

The stakeholder materiality analysis is the first level of integration and should be conducted simultaneously for quality, cost, products, environment, health and safety and social responsibility. The analysis helps to shape a comprehensive set of goals and objectives, as well as the overall scorecard of the organization. When conducted holistically as a part of the organization’s annual setting of goals, objectives and budgets, it seamlessly integrates into how the business operates. A similar approach was developed and fine-tuned by Omnex for Ford Motor Company in a process called the Quality Operating System.

Step 2: Look Out! (Integrated Risk)

In parallel with the Stakeholder Materiality Analysis, the risks to the business are analysed through an Integrated Risk Assessment. This means the identification and quantification of quality, cost, product, environment, health and safety and social responsibility risks, in terms of their potential affect on the company’s strategic, production, administrative and value chain processes. The risk measures developed need to be valid for all the different types of risks and different entities of the business, and mitigation measures identified.

The first two steps of Stakeholder Analysis and Risk Assessment are requirements of the new ISO 9001, ISO 14001 and ISO 45001 (formerly OHSAS 18001) standards slated to come out in the next few years. For example, in the new ISO 9001 that is planned for release in 2015, it is called ‘Understanding the Needs and Expectations of Interested Parties’ and ‘Actions to Address Risks and Opportunities’. The evolution of the ISO standards is indicative of a shift in global mind-set (since ISO represents over a 100 different countries) to prioritising stakeholder engagement and risk management.

Step 3: Dig Deep! (Critical Processes)

In step 3, the Stakeholder Materiality Analysis and Integrated Risk Assessment are used to identify critical business processes, using the Process Map of the organization. It is likely that the most critical processes – in terms of their impact on SQELCH issues – will include Governance & Strategic Planning, Product or Service Development, Product or Service Delivery, Supply Chain Management, and Customer Chain Management. There may also be others, depending on the particular business or industry sector. This Critical Processes list should also include the most relevant sub-processes.

Step 4: Aim High! (Innovation & Value)

Step 4 entails the Innovation and Value Identification element. Using the Net Zero/Net Positive strategic goals, or others like Stuart Hart’s sustainable value framework, each of the critical processes is analysed for opportunities to innovate. Opportunity analysis is followed by idea generation and screening and the creation of a Breakthrough List. This is the chance for problem solving teams, Six Sigma teams, Lean teams, and Design for Six Sigma teams and others to use improvement tools to take the company towards its chosen transformational goals. The improvement projects will continue for a few months until they are implemented and put into daily practice.

Step 5: Line Up! (Systems Alignment)

In Step 5, the requirements of the various SQELCH standards most relevant for the organization, together with the transformational strategic goals, are integrated into the management system of the organization, including the business processes, work instructions and forms/checklists. Process owners working with cross-functional teams ensure that the organizational processes are capable of meeting the requirements defined by the various standards and strategic goals. This is followed by training to ensure that the new and updated processes are understood, implemented and being followed.

Step 6: Think Again! (Audit & Review)

Integration has one final step, Internal Audit and Management Review, which creates the feedback and continuous improvement loop that is essential for any successful management system. This means integrating the value creation process into the governance systems of organization, including Strategic Planning and Budgeting, Management or Business Review, Internal Audits, and Corrective Actions. This is what will ensure that implementation is happening and that the company stays on track to achieve its transformational goals.

Words Count, Actions Matter

To conclude, we believe Creating Integrated Value, or CIV, is an important evolution of the corporate responsibility and sustainability movement. It combines many of the ideas and practices already in circulation, but signals some important shifts, especially by using the language of integration and value creation. These are concepts that business understands and can even get excited about (whereas CSR and sustainability tend to be put into peripheral boxes, both in people’s heads and in companies themselves).

More critical than the new label or the new language is that CIV is most concerned with implementation. It is a methodology for turning the proliferation of societal aspirations and stakeholder expectations into a credible corporate response, without undermining the viability of the business. On the contrary, CIV aims to be a tool for innovation and transformation, which will be essential if business is to become part of the solution to our global challenges, rather than part of the problem.

Article reference

Visser, W. and Kymal, C. (2014) Creating Integrated Value: Beyond CSR and CIV to CIV, Kaleidoscope Futures Paper Series, No. 3.

Endnotes

[1] Organizational governance, human rights, labour practices, environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement and development

[2] It is interesting to note that the revised ISO 14001 being planned for release in 2016 includes a life cycle perspective for all aspects of operations including product design and delivery.

[3] This is captured eloquently in John Elkington’s book, Zeronauts (2012)

Download

[button size=”small” color=”blue” style=”download” new_window=”false” link=”http://www.waynevisser.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/paper_civ_wvisser.pdf”]Pdf[/button] Creating Integrated Value (CIV) (paper)

Related pages

[button size=”small” color=”blue” style=”info” new_window=”false” link=”http://www.omnex.com/”]Page[/button] Omnex (website)

[button size=”small” color=”blue” style=”info” new_window=”false” link=”http://www.kaleidoscopefutures.com”]Page[/button] Kaleidoscope Futures (website)

Cite this article

Visser, W. and Kymal, C. (2014) Creating Integrated Value: Beyond CSR and CIV to CIV, Kaleidoscope Futures Paper Series, No. 3.